This is the surprise twelfth post in a series of Ace Attorney reviews, and I recommend reading the others before this. This post contains spoilers for The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles and all other Ace Attorney games. Thanks for reading!

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Part One: A History Class & The Adventure of the Great Departure

- Part Two: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle & The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band

- Part Three: Farewell, My Turnabout and The Adventure of the Runaway Room

- Part Four: The Adventure of the Clouded Kokoro and The Memoirs of the Clouded Kokoro

- Part Five: The Adventure of the Unspeakable Story

- Part Six: The Adventure of the Blossoming Attorney, Susato and the Defendant Defence

- Part Seven: The Reaper of the Bailey and The Return of the Great Departed Soul

- Part Eight: Twisted Karma and His Last Bow, The Resolve of Ryunosuke Naruhodo and Variations on a Theme

- Conclusion

Introduction

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures was first released in Japan in 2015, under the name Dai Gyakuten Saiban. A brand-new Ace Attorney spin off game from series creator Shu Takumi, the build up for the game was met with a huge amount of hype. However, poor sales, criticism of the game’s abrupt ending and its release on a dying handheld meant that, much like the similarly placed Ace Attorney Investigations 2, the game wouldn’t soon find itself being released outside of Japan, even after the release of a sequel in 2017.

In between the original Japanese release of Dai Gyakuten Saiban and the English release of The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles, I have worked on a huge series of reviews of the entire Ace Attorney series, along with doing what I call a “reverse Naruhodo” (studying Japanese and moving from London to Japan for a year). Now, finally, with a worldwide release and a definitive version of these two games, I can finally write about them to a wide audience and give them their proper place within the Ace Attorney series.

Due to the length of the games, I have given this review a table of contents that should make it slightly easier to read and navigate. So, without further ado…

Part One: A History Class and The Adventure of the Great Departure

The Great Ace Attorney Adventures opens with a description of Japan’s Meiji Period, placing the game in a brief historical context, and will go on to use historical elements of Anglo-Japanese relations – such as extraterritorial rights for foreign criminals – as major plot points. This is the first Ace Attorney to have such a definitive placement within the real world. Previous games in the series have not only been set in a near-future Japan that is separate enough from the real Japan to become Los Angeles in the localised versions, but have also used fictional countries when the topic of international relations is discussed.

The Great Ace Attorney benefits hugely from situating its story within the real world because it allows the series to tackle themes like immigration and racism in a way that it couldn’t before, while the historical setting prevents those from becoming overpoweringly politically relevant in a way that a series best known for goofy murders perhaps couldn’t handle.

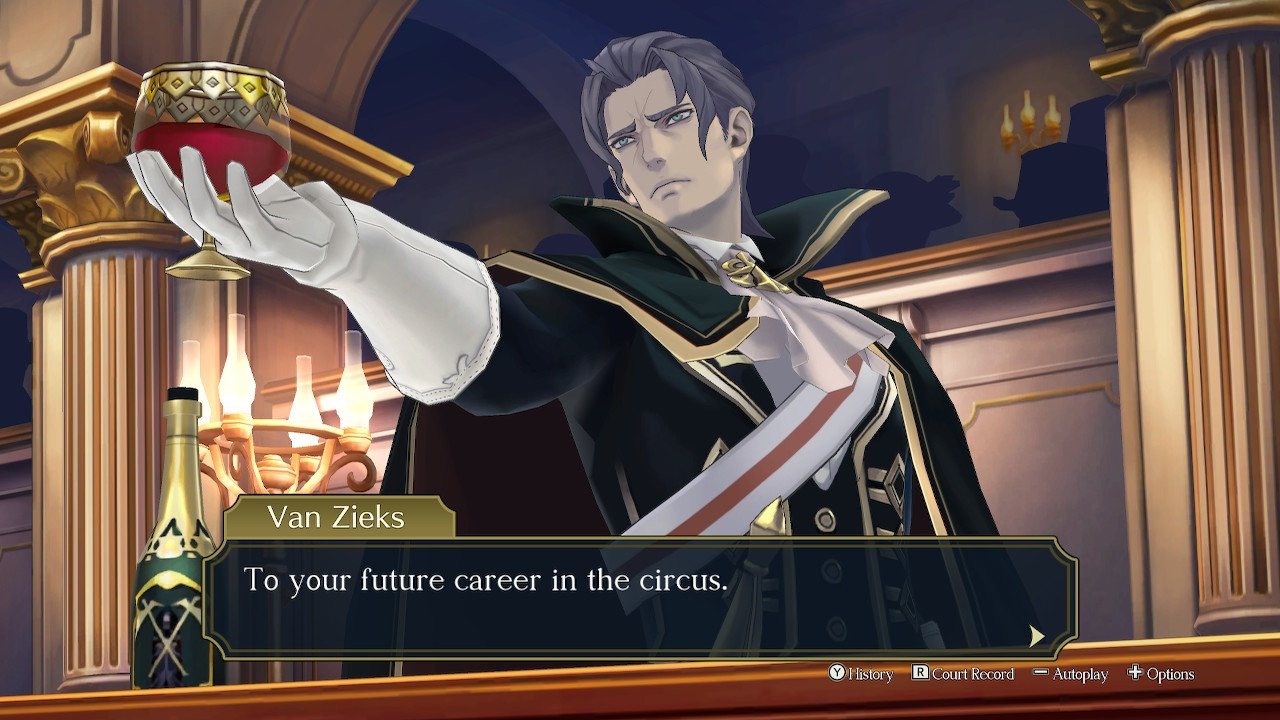

The first case is a perfect example of how the games will go on to use and play with these ideas of political relations in a way that befits the series. The crime, of a visiting British professor murdered in a Western style restaurant in Tokyo, is initially pinned on the new playable character, Ryunosuke Naruhodo. However, the true culprit is of course one of the witnesses, a British exchange student who goes by the moniker Jezaille Brett. Brett’s main attribute is one of patronising contempt towards the Japanese – not only does she know that the extraterritorial rights granted to her by the most recent Anglo-Japanese treaty mean that even if she is accused of the crime she will walk free, but her attitude is one of a common imperialist sense of superiority that was common of British citizens during the time of the Empire. It’s a good way of making her, as well as other British characters in the game like new prosecutor Barok van Zieks, instantly dislikeable to the player, while conveying the sense of powerlessness that would have been felt by a citizen of a country like Japan in the face of the British Empire.

Of course, diving into a historical time as fraught as this raises a number of questions as to what you choose to include and what you don’t. Although the British characters in The Great Ace Attorney are often dismissive of Ryunosuke and other Japanese characters like Natsume Sōseki, there is a sense that the overwhelming character of the Imperial British is one of nothing more than a slight superior snootiness, rather than the often much more virulent racism and the much more present imperialism and colonialism, given that this game takes place at the height of the British Empire. While some discussion on the game has mentioned the game’s racism as a negative, I think not including it would have been a disingenuous and false representation of the period, and that the game is often walking a tightrope of being accurate while not being unpleasant to play. Similarly, the game being set mostly in England means that it can often cast its eyes over the fact that Japan itself was in the process of Empire building. This was, as the game does dutifully hint at, in part of course, a response and a defence from Western Imperialism, but it’s hard to fully paint Japan as nothing more than a victim in this game when it’s set only around a decade away from the colonisation of Korea. Perhaps it’s for this reason that Seishiro Jigoku, a Japanese man who does awful things partly because of pressure from a stronger Western power, is included in this game, but it’s hard to say that the game is flawless in its representation of this period. This is definitely a sanitised, Ace Attorney vision of the past, and if you’re willing to accept the simplification of this period, it works. However, it does perhaps enlighten why the series has traditionally stayed away from depicting real countries and events in the past.

Even though The Adventure of the Great Departure successfully integrates the political into a standard Ace Attorney case, it’s a shame that the actual case behind it isn’t very good. The case’s opening borrows heavily from both the original game and to an even greater extent, Apollo Justice. Instead of Phoenix Wright or Mia, the character who acts as Ryunosuke and the player’s guide is Kazuma Asogi, an older and slightly more sanctimonious student, who is planning a study abroad trip to Great Britain. Asogi, like Phoenix in Turnabout Trump, shows the player a far more confident character to aim towards. Ryu himself is a ball of nerves, with eyes darting every which way, so it’s a classic bit of game design to show the player something to aim towards, while in the final level subverting the dynamic between these two characters as a way of showing progress.

The problem is, even with all the extra case time that this game has over, say, The First Turnabout or Turnabout Trump, Asogi isn’t really that much more interesting or developed than Mia is. It would be unfair to compare him to Phoenix, who carries the weight of player expectations and memory, but Mia in the first game actually ends up being relatively similar to Asogi in her meagre half hour of screentime. They’re both confident, occasionally slightly doubtful of the main character’s intelligence, but believe them to be able to achieve victory when push comes to shove. They even deliver pretty much the same speech at the end of the case about believing in your client.

If the game doesn’t use the extra time to develop the characters, the question becomes what it does use it for, and the disappointing answer is really not much. The case in question is actually quite simple, but it’s drawn out by a number of twists and turns that are really unnecessary. In general, the whole case is a bit too dramatic for a first case, setting the stakes somewhere similar to Spirit of Justice’s first case. In particular, one moment where Ryu’s abruptly introduced power of recollection is used seems particularly cheap, especially as this ‘power’ is never mentioned again in either game.

This isn’t to say the case doesn’t have promise. Indeed, the idea of using a poison not yet recognised by Japanese courts is really clever. But these moments of brilliance are mainly hidden or bogged down by annoying testimonies and drawn-out moments of unnecessary drama.

There is one other way in which the case does give a good first impression. Of all of the new Ace Attorney games, this duology best justifies the move away from 2D sprites and into a 3D engine. Mainly, this is thanks to character designs by Kazuya Nuri, who previously worked on Apollo Justice and Professor Layton vs Ace Attorney. His designs completely nail the tone of the game – one that walks the line between the more restrained designs of the original Trilogy while maintaining the emphasis on 3D movement that Takuro Fuse is known for. This all leads to a game which is beautiful to look at, more so than perhaps any game in the series.

Part Two: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle & The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band

The game’s second case, The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band, is the first Ace Attorney case to lack any kind of cross-examinations, taking place completely in the investigation segment of a standard Ace Attorney game. It’s also the case which introduces Herlock Sholmes, an analogous figure for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous Victorian era detective Sherlock Holmes.

Holmes is one of the most adapted figures in literary history – even the Ace Attorney misspelling of his name is in itself a reference to one of the first non-Conan Doyle Holmes stories, written by Maurice Leblanc in 1906. Still, as an adaptation of the Conan Doyle character, it seems to make sense that Sherlock’s name has been changed, given that Takumi’s interpretation of the character seems to take only the lightest of influences.

Sholmes in The Great Ace Attorney bears very few of the traits of the original character. In fact, only really one remains, which is the power of deductive reasoning, as demonstrated in the new mechanic “The Dance of Deduction”. We’ll talk more about that later, but first, let’s talk about Sholmes, both as an Ace Attorney character as well as in relation to the original novels.

Sholmes himself seems a unique character for a core cast member of an Ace Attorney game. An investigative partner, he’s sillier and indeed seems at first stupider and more out-there than most of the central characters of Ace Attorney. With perhaps a few exceptions (Fulbright comes to mind), the core cast of an Ace Attorney game is more down-to-earth than the witnesses, in both look and mannerisms. Sholmes throws this on his head by being an eccentric, dancing, famous great detective. In Speckled Band, you almost couldn’t hope for a better character introduction than all the weird positioning Sholmes takes in the environments during investigations. Coupled with the stylish and energetic Dance of Deduction, almost every encounter with Sholmes adds a shot of much needed energy and pace into The Great Ace Attorney, a game that otherwise finds itself preoccupied with achieving a darker tone than most of the other games in the series.

The problem with Sholmes is when the game tries to reconcile that idiotic but charming persona with the game’s darker side. Sholmes is a great detective before the game starts, and thus knows much more about London and its darker sides than Ryu probably ever will. So, because of this, we get to a problem that Ace Attorney often faces when it introduces non-playable characters that are cleverer than the game’s protagonist – if they’re so smart, what are they doing fucking around all the time? Sholmes consistently feels like a character who is holding back information and not letting Ryu in, but his motivations for doing so are often annoyingly oblique, even when explained fully. The reason he hides the truth about Asogi is fine, but more often than not the game misfires each time Sholmes is hinted to be hiding some dark secrets about the Baskervilles or the Professor.

Phoenix in Apollo Justice is probably the best counter-example to this. For most of the game it’s clear that Phoenix is plotting something he isn’t letting on, but his persona remains mainly pretty affable. However, the contrast between Phoenix’s morally complex deeds and his jokiness isn’t that harsh. It’s totally believable from the first case of that game that Phoenix is hiding something underneath his nice exterior. When, in The Return of the Great Departed Soul, Herlock says that sometimes great detectives have to lie, it adds a layer of moral complexity to his character, but it’s slightly difficult to reconcile with the Herlock you knew. It’s too much of a tonal whiplash.

Even more disappointingly, the game never really follows through with this kind of moral greyness as it did with Phoenix. The reveal that Phoenix forged the card is really good, because it does make you think twice about a likeable character. With Herlock, the game keeps skirting around the fact that he might not be as great as he seems, only to eventually give in and say ‘nah, he is actually lovely, don’t worry’. While I think this is probably the correct way to treat Herlock’s character, it could have done without the constant hints that there might be something more to him. It’s indicative of a problem shared by much of The Great Ace Attorney – a constant state of hinting that something deeper is wrong, without quite enough of a follow through.

A dark side to Herlock wouldn’t be completely out of place, though, as the Conan Doyle creation is known for his prickly personality and drug abuses. Indeed, it’s only in later stories that Sherlock gets any kind of humanity at all, including, according to the Conan Doyle Estate, ‘a respect for women’. However, despite the constant references to them, it’s doubtable how much Takumi even likes the original Sherlock Holmes stories. Not that I would blame him, of course. Despite being a British fan of murder mysteries, I have never seen the appeal in the Holmes stories, nor in any of their many adaptations.

However, there are certain elements that go a bit beyond loving reference and into outright mockery. Several of Sholmes’ incorrect deductions are the real solutions to Conan Doyle mysteries, including the one from the case in question, which correctly points out the absurdity of the solution to the original Speckled Band. Of course, given the solution to some Ace Attorney cases, it seems a bit rich to throw such shade on one of the progenitors of the murder mystery genre. This is including the solution to The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band, which replaces the snake of Conan Doyle’s original with the small cat of a Russian ballerina. The case opens with Sholmes finding Ryunosuke locked in the wardrobe of Asogi’s cabin, having sneaked in as a stowaway. Sholmes informs us Asogi has been killed, and Ryu and Susato – Asogi’s judicial assistant – must now solve his murder before Ryu is turned in to the police when the boat docks. This sets up a good, high-stakes investigation case, with no courtroom to be seen. It’s also the second time the game has drawn inspiration from Ace Attorney’s past, with Asogi’s death in the second case mirroring that of Mia’s in Turnabout Sisters.

As a story, Unbreakable Speckled Band is a step up from Great Departure. Sholmes’ introduction is well-handled, the stakes feel more personal with Asogi’s death and the solution to the locked room is undoubtedly clever. This case also has one of the more interesting characters in Nikolina, the Russian ballerina who is escaping from her troupe by hiding onboard the ship.

While I admire the Nikolina storyline in theory, in practice there are some problems with it. Nikolina is the true ‘culprit’ of the case, pushing Asogi over when she thinks he’s going to call Detective Hosonaga to send her back to Russia. It’s obvious that Nikolina is in the wrong here, but it’s completely easy to see why she panicked – she’s a young refugee who is escaping from an abusive situation and has no reason to suspect that Asogi is calling Ryu instead of the Detective. I tend to enjoy the tragic side of Ace Attorney – it’s something I think Takumi generally handles well. But he tends to do this by writing the situations in a way that doesn’t totally let the culprit off the hook, while sparing them a little, emotionally.

My favourite example of this is Jean Greyerl from The Golden Court. Like Nikolina, she kills someone who was actually trying to help her, because of mistaken information. However, in a final twist, Takumi reveals that the person she thought she killed was already dead. This doesn’t take away from the gravity of what she tried to do, but it does show a little kindness to her by not having her actually kill her mentor. In The Unbreakable Speckled Band, however, the game almost revels in revealing that Nikolina is more and more responsible for Asogi’s death, to the point where it almost feels cruel to her to keep pushing so hard. Indeed, this character is responsible for trying to cover up a murder, but the deftness of touch I normally associate with Takumi’s writing is missing, replaced by a need to reaffirm what a great person Asogi was, rather than recognise the tragedy on both sides of the murder.

The other problem with the case is how it plays in general. Ace Attorney games are not traditionally known for their investigation segments. Every game since Justice for All has tried to do something to make them less of an on-rails point-and-click segment, but no game has relied solely on the investigations, because they act as the cool-down between the intensity of the courtroom set pieces. The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band tries a few ways to fix this, cribbing slightly from the Investigations textbook of a rising tension rather than a rise and fall pattern, but joyfully being shorter than many of the cases in that spin-off series. It also introduces a new mechanic, the Dance of Deduction, but leaning on that so heavily reveals the weaknesses of that mechanic.

The first problem with a fully-investigation case shows in how the locked door solution is revealed. Although I praised the solution for being clever, the answer has to be literally handed to the player, because the investigation segment doesn’t have the tools to reveal information to the player in a way that allows them to work it out logically, unlike the courtroom segments.

The Dance of Deduction, which should allow the player to work stuff out, is sadly too shallow to give the case the moments of deductive reasoning it sorely needs. I’m all too happy to heap praise on the mechanic for its presentation, which borrows heavily from the style of Takumi’s previous game Ghost Trick. What’s especially impressive is how the game is not content to rest on its laurels creatively with the presentation of this mechanic. Even though it arguably reaches its peak in The Return of the Great Departed Soul, the final case’s Dance is still aiming to surprise.

Sadly, when you get down to brass tacks, it’s undeniable that this is all flash with little substance. The gameplay is basically just an extension of the point-and-click investigations, rather than anything that requires logical deductions. It’s slightly better and far less tedious than the Perceive function, but compared to the Magatama, the Dance of Deduction falls sadly flat. Because the game highlights the items you can click on, the contradictions you have to find in Sholmes’ ‘testimony’ are always solved by just tilting the camera slightly and finding the thing you can click on. Not only that, the Dances happen at most once per chapter, which means that they don’t even have the impact on investigations that the Magatama does. Compared to the mechanics that underpin Investigations’ cases, the Dance looks even thinner as a gameplay mechanic.

The Dance of Deduction basically sums up how I feel about The Adventure of the Unbreakable Speckled Band. It’s mostly likeable and engaging, but pretty shallow on a gameplay level.

Part Three: Farewell, My Turnabout and The Adventure of the Runaway Room

Ryu and Susato finally arrive in London in the third case, The Adventure of the Runaway Room, which stands out as one of the better cases in the game, and one that reinvents and plays with the idea first introduced in Farewell, My Turnabout – that of a guilty client who you have to defend. The case does a lot different with the same premise, but it’s worth noting that as of this point, The Great Ace Attorney has struggled to fully reinvent the Ace Attorney formula, instead only really playing with it lightly. This will become even more apparent as we move into the second game, but it’s worth keeping an eye on the similarities now – the links in Great Departure to Turnabout Trump and The First Turnabout and the ties in Unbreakable Speckled Band to cases like Turnabout Sisters.

Another similarity comes in with the character of Lord Mael Stronghart. From the moment you see his double-breasted suit, Stronghart links himself to a certain type of Ace Attorney villain, personified by Damon Gant and Inga Khura’in. I think it’s not necessarily a problem that Stronghart identifies himself as a villain so quickly, given that you then have to work out in what way he will become involved, but honestly his motivations and ties to the final case are clear relatively quickly. Gant and Stronghart’s similarities are something we’ll get to when talking about the game’s conclusion, but Stronghart himself is worth mentioning now given the shadow he casts over the game with his every scene.

Unlike the at first innocent-seeming Matt Engarde, the defendant in this case, Magnus McGilded, is far more suspicious from the outset. Because of this, Runaway Room removes some of the tension that defines the beginning of Justice for All’s finale. However, what sets Runaway Room apart is that instead of playing out as the thriller the earlier case is, it sets out to focus more on the moral aspect of defending a guilty client. It does this by removing the coercive element of Maya being kidnapped and tying the dilemma instead to Ryu’s sense of loyalty to Asogi.

The new prosecutor, Barok van Zieks, so-called “Reaper of the Bailey” plays into this. We’ll talk more about his actual character later, but for the purposes of discussing this case, the important thing is that although he’s incredibly racist towards Ryu, you know that he’s in the right when it comes to the case at hand. These dynamics all play together in ways that give the case some real depth and complexity. Ryu has to get a not guilty verdict in order to carry out what he perceives as Asogi’s mission. However, a personal sense of justice would mean betraying your client and exposing his deception. Couple this all with the sense of duty towards your client that Asogi espoused as the reason for being a defence attorney only two cases earlier and a real dilemma starts to emerge.

That isn’t to say that the case doesn’t have the thriller aspect that Farewell did so well. Most of McGilded’s lies are actually performed halfway through the case, when he enlists pickpocket Gina Lestrade to plant fake evidence inside the crime scene, a London carriage which has been placed at the courtroom. This leads to some fantastic drama where even the act of examining evidence is filled with a kind of heart-sinking tension, where you realise you’re going to be forced to argue a case based on evidence you know is fake – a similar feeling to the flashback case in Turnabout Succession.

The other element that plays into this web of a case is the jury, a new mechanic that serves as an update of the mob-examination mechanic from Layton vs. Wright. The jury in this case serve a kind of dual purpose. The first is in introducing Ryu to London, and filling it out with an extensive array of inhabitants early on. Runaway Room does this so much more effectively than The Foreign Turnabout by giving faces and personalities to the crowd of Londoners who are so against Ryu. Both Van Zieks and the jury are racist and condescending towards Ryu, and the fact that even your client is untrustworthy compounds the feeling of hopelessness. What’s more, the Old Bailey actually looks grand and imposing compared to any other court in the series. London, then, within the first five minutes of the case, is already better fleshed out than a country like Khura’in ever is, because we actually get face to face with its people.

The jury are also there to introduce the new summation examination mechanic. It’s basically the best kind of new Ace Attorney mechanic – an update and a remix of the cross-examination system, this time using multiple witnesses who each talk over each other and occasionally contradict each other. Sure, at times the strategy remains the same (start by pressing people who seem to be saying unrelated statements until it becomes blindly obvious), but all in all I think the summation examination does add a layer of depth to courtroom proceedings, as well as one that thematically embodies the ‘turnabout spirit’ that is referenced in the game’s names.

Part Four: The Adventure of the Clouded Kokoro and The Memoirs of the Clouded Kokoro

It is foolish to speculate on the behind-the-scenes workings of video games – the thought process of Takumi and his crew is impossible to ever really work out. But the placement of The Adventure of the Clouded Kokoro and The Memoirs of the Clouded Kokoro as split between the two games is a weirdness that is probably attributed to the way in which Chronicles was first written and then the necessities of how it was finalized and released in two halves. However, I am here to rectify this mistake in my review – these cases together form the absolute best part of both games, and two of the best cases in the entire Ace Attorney series.

The reason these cases succeed so well is that they’re brilliant at communicating some of the more interesting themes of Chronicles; specifically, the overlapping concerns of race and class and how they pertain to the setting of Victorian Britain. Both cases do so surprisingly subtly, using for their backdrop a small block of flats in London and its various residents. The most important of these is the real-world novelist Natsume Sōseki, who is responsible for some of my favourite works of Japanese literature and who lived in London between 1901 and 1903.

Sōseki’s cameo in this game allows for Takumi to make fun reference to Japanese literature in the same way as he plays with British literature, but it also serves a more fundamental purpose of commenting on the immigrant experience. The real Sōseki was similarly miserable during his trip to London, likening himself to “a dog amongst a pack of wolves”, feeling upset at the differing ways that Londoners saw the world and eventually suffering a nervous breakdown. By including a more extravagant and open Sōseki in Chronicles, Takumi makes overt the emotions that have perhaps been concealed or couched by Ryu and Susato in Britain. Sōseki might be extreme in his emotional outbursts, but one must imagine that this extremity is only caused by the combination of overwhelming paranoia from living in a country that has abandoned you and the joy of connecting with fellow countrymen. For many players, both in Japan and overseas, this will not be a familiar feeling, so Sōseki’s over the top mannerisms are a welcome way of making this obvious to those without the experience of living overseas.

In both cases, Sōseki tends to refer to his existence as “cursed”. It is tempting to read this curse as relating solely to the explicit “convict’s curse” – that is William Shamspeare’s attempts to murder the people living in the apartment that used to belong to his former cellmate Selden. However, read in another way, the curse becomes a synonym for both the immigrant experience and the curse of poverty. It’s in the discussion of the effects of poverty where these cases shine, because much like Recipe for Turnabout, both Kokoro cases illuminate in multiple ways the powerful effect of money, and more specifically in the British context, class.

The first case, Clouded Kokoro, uses two couples to illuminate the importance of class and status in Victorian Britain. The first is the Garridebs, whose marital spat ends up being the annoyingly unlikely cause of the stabbing case for which Sōseki is accused. John Garrideb and his wife Joan manage their three-storey house on Briar Road, many of the windows of which have been sealed up due to Britain’s famous window tax policy, which economist Adam Smith noted had a disproportionate effect on the poor. John is a former military man and keeps the proof of his service in prominent position in his flat, despite being dismissive of it in his dialogue. His wife Joan poses as his maid, a way of keeping up appearances. The Garridebs are desperately trying to cling onto an image of a middle-class life that was promised to military men, especially before the Industrial Revolution. Class themes will continue to permeate throughout both games in the series, most obviously later in Adventures with the character of Graydon and his struggle to escape from the lower classes with his criminal activities and gaudy outfits.

To a lesser extent, we can see the effect of the changing state of British society in the witnesses Pat and Roly. Roly Beate is a policeman working for Scotland Yard, but he’s so overworked by the demanding job he ends up moving the crime scene just so he can have a date with his girlfriend. Pat is obsessed with Roly’s job because it implies status and respect within London society, even if it doesn’t come with good hours or a huge paycheck. Meanwhile, officers at the higher end of Scotland Yard like the constantly disgruntled Tobias Gregson, are not beset by the same hours or constraints as those on the bottom of the rung.

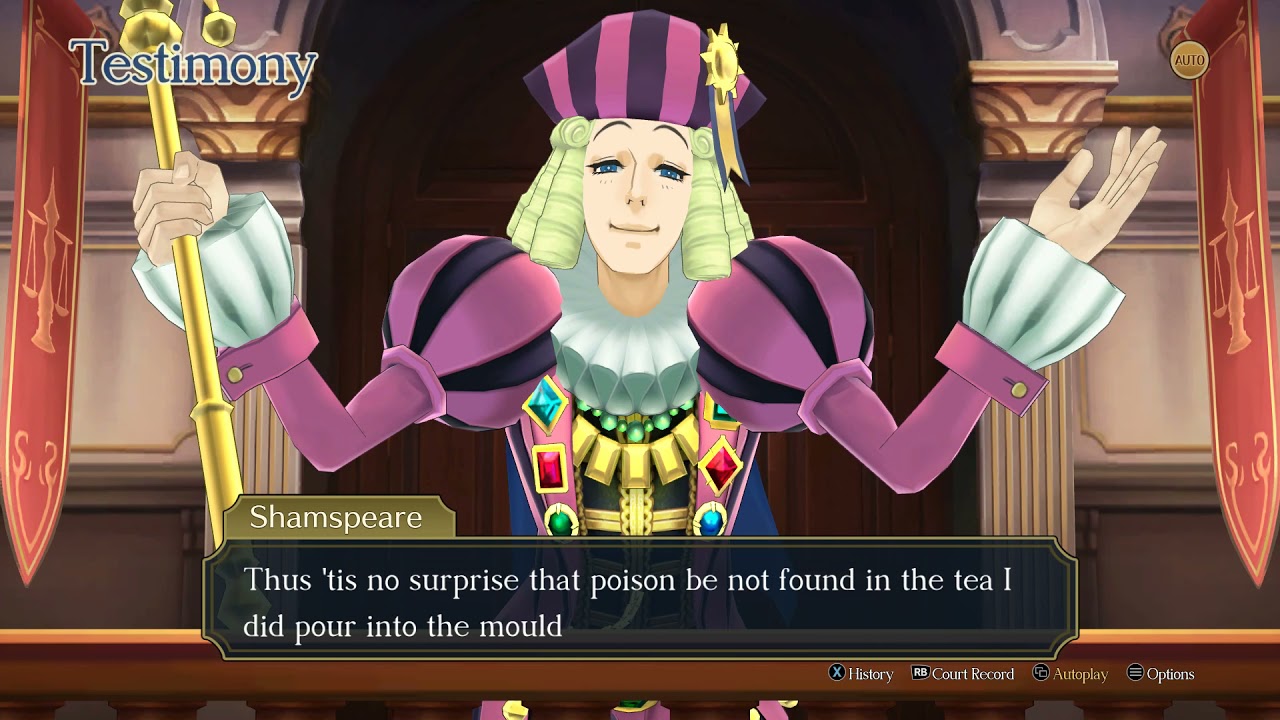

The preoccupation with money continues into Memoirs, where William Shamspeare, the case’s ostensible victim, is accused of stealing gas from the wealthy Alamont Gas Company. His ingenuity is presented as a criminal act, but it’s hard not to feel some sympathy for his critique of having to pay for necessities such as warmth and light, a sympathy shared by some other members of the gallery.

What really elevates the two cases is that money and class, or even alienation, aren’t their only themes. Interwoven with this is a further theme of romance and the things people will do for love. Ace Attorney has mostly turned away from covering the topic of romance, but here most of what happens on Briar Road during these two cases are in someway motivated by love – the marital spat of jealousy that causes the Garridebs’ arguments, Roly Beate moving the body to spend more time with his wife and of course Olive Green poisoning Shamspeare to avenge the death of her lover. It’s interesting to see Ace Attorney tackle love, because it’s so often used as a motive for murders in other murder mystery series. Here, Takumi doesn’t just glance at it, but explores love as a motivation in three different ways, leading to some actually interesting portrayals of the things that love can motivate us to do.

The cases themselves are also good apart from this, although Memoirs is undoubtedly the stronger. The first Clouded Kokoro has the unfortunate job of introducing 221B Baker Street and Iris Wilson. Baker Street has the same problem that I have with Nuri’s design for the Wright Anything Agency in Apollo Justice – it’s simply too twee to act as a hub for the characters, offering no real escape from the intensity of the other environments. Luckily, this game also includes the attic, which is a much better home base for Ryu and Susato, reminiscent of the similarly cosy attic space from Persona 5.

I’m less of a fan of Iris Wilson, who is the final member of the game’s core cast to be introduced. The first problem with her actually starts way back in Unbreakable Speckled Band, when Sholmes is first introduced, in the use of future technology within Chronicles. Professor Layton vs. Phoenix Wright, and even The Adventure of the Great Departure do a really good job of demonstrating some of the problems of crime solving in the past – the lack of technology like luminol, fingerprinting and the phone call. However, Takumi uses the steampunk aesthetic of Sholmes and Iris to completely cheat this, even introducing technology, like hologram phone calls, that don’t even exist in the future of the mainline series. I’m not opposed to Ace Attorney using fictional technology – this is, after all, a series where spirit channelling is commonplace. However, it is slightly disappointing to see this opportunity for more inventive mystery solutions squandered, and often jarring to see Sholmes wonder in awe at something like a stereoscope when only a few cases later he will invent a hologram.

That isn’t really about Iris herself, though, who is the latest child genius in the vein of Pearl Fey from the original trilogy. Pearl is only a year younger than Iris, so acts as a pretty good comparison point. Pearl is perhaps a little annoying in her naivety, but it is that character trait that makes her a well written child prodigy. She isn’t precocious, nor acts like an adult. She’s believably childish while still happening to be incredibly gifted at spirit channelling. On the other hand, Iris is 10 years old, an inventor, a writer and has a medical degree. Somehow. Now, a character could be a genius prodigy like this in an anime game – if they were aged up a bit. In fact, Iris does act like more of a teenager than a 10-year-old. Aging her up would alleviate the strain on my suspension of disbelief while also just generally making her better written. I often found myself drawing comparisons in my mind between her and Simon Blackquill, as characters with promise too bogged down by extraneous details intended to make them more interesting. As she is, I struggle to see Iris as a genius, but more importantly I struggle to see her as a child.

The other big problem that both cases highlight within Chronicles is asset reuse. Now, this is a bit harsh to a game with a small budget, but there is a problem with the small sample pool of jurors that Chronicles keeps invariably returning to, which is that it makes London look small. The game attempts to create a picture of a huge city that dwarfs anything either Ryu or Susato have ever seen but constantly fails to deliver on this. The first time stepping inside the Old Bailey is one thing, but after that, places like the Great Exhibition only end up being one small screen to investigate, even after being hyped up for the duration of both games. Further, the jury are always too involved in the case. Three of the jurors in Adventures of the Clouded Kokoro were in the area of the case on the day of the crime, and one is from a previous case. It is perhaps an inevitability for a small-scale series like Ace Attorney, but it is noticeable.

If I can offer Clouded Kokoro one more bit of huge praise, it’s that the case finally manages to solve a problem that has been plaguing Ace Attorney all the way up to Spirit of Justice. I wrote in my summation review of the series up to Turnabout Time Traveller that the games have never really cared about themes or messages, and that this is illustrated by the fact that the series’ two most oft repeated mantras; to believe in your client above all else, and to believe in the truth above all else, are mutually exclusive. However, in this case, Takumi has the revelation that joins these two viewpoints together – what matters most is faith in yourself: resolve to know what the right direction to pursue is. In Great Departure, Asogi tells Ryu that the right thing is to believe in your client. In Runaway Room, Ryu is already faced with a situation where this becomes troublesome, and in Clouded Kokoro, Ryu is now forced to choose which Ace Attorney mantra he needs to go for. The answer, of course, is to look inwards. Neither approach is one hundred percent correct all the time – instead, the correct thing is to trust yourself enough to know who and what to trust.

Part Five: The Adventure of the Unspeakable Story

And so, we come to the final case of the first half of The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles, which caused some controversy when it was first released, given the open-ended nature of the ending. Indeed, this case does function more akin to other titles’ third cases – an “end of act two”, where the dynamics of the Baker Street crew are set up and the game’s proper intentions are revealed. Because of this, the case starts quite slowly, making sure the character dynamics are given some time to breathe before it makes the first startling revelation – that of the note to McGilded on the back of the music disk.

McGilded is a character whose impact and strength is only really felt here, after his death. In Runaway Room, there is clearly more to McGilded than is apparent on the surface, but Ryu is too new to London to really realise this, beyond seeing Van Zieks’ dogged determination to put McGilded behind bars having caused his return to the courtroom after five years. The atmosphere to Unspeakable Story, then, becomes not unlike another Takumi finale – Turnabout Succession. Like that case, there is the shadow of a criminal met earlier in the game that hangs over the episode, fleshing out that character even when he isn’t present on screen. Both cases even have a moment of great mysterious tension that ultimately goes nowhere – Misham’s paintings and Susato knowing about the Baskerville story respectively.

One of the biggest problems with Unspeakable Story, however, is its reliance on some slightly lazy twists – moments that read well in theory but are a little bit annoying, like Sholmes knowing exactly when to deliver the cat flap maker to Ryu. Many of the laziest revelations in these games, however, come from the evidence investigation mechanic. First introduced in Rise from the Ashes, Chronicles is the first Ace Attorney game to make full use of the ability to examine evidence from all angles. This quickly becomes a double-edged sword. Runaway Room is great at showing how this can excel, with the examination of the crime scene leading to the twist about McGilded’s forgery in a really natural way. However, in a lot of other cases, it becomes a case of just receiving new evidence, turning it around once and finding the thing that Scotland Yard and Van Zieks just somehow managed to miss that turns the case around for good. In earlier games, new evidence that at first seems irrelevant had to be proven useful by comparing it against or alongside testimony from witnesses. However, here, most new evidence is just twisted around a few times before the way in which it should always have been used becomes blindingly obvious.

It’s only in this case that the game finally reveals one of the elements that will become vital in the sequel, which is the element of international intrigue and governmental communication between England and Japan. Because of the lack of the personal stakes that Asogi will end up bringing to this plot point, in Unspeakable Story it does veer a bit too close to the faceless “Phantom” of Dual Destinies. Luckily, the personal element is injected through the tragic story of Graydon and his father, who was the victim in Runaway Room. Graydon, seeking revenge on McGilded, was responsible for both his death and the death of the pawnbroker Pop, in an attempt to save himself from being found guilty of the sale of government secrets. Van Zieks, at the end of the trial, notes that Graydon has become the same kind of monster that McGilded was, setting up a theme that will be hammered home a lot in Resolve. However, I’ve never really gelled with this kind of message – one that revenge makes you an equivalent kind of monster. Although Graydon is a killer, he’s still locked in a struggle to try and escape the influence of a far worse person, which makes him a subtly different kind of murderer. Equating the two, as Chronicles does time and again, can remove some of the nuance and tragedy from a situation.

The final thing to note on this case, before The Great Ace Attorney Adventures comes to an end, is Tobias Gregson, the game’s detective. Gregson here demonstrates the one time having multiple witnesses on the stand is used in a particularly novel or interesting way when he negotiates a deal with Graydon on the stand. It also serves dual purpose of making Gregson a pretty interesting detective – he’s more hard-boiled than perhaps any of the detectives seen in the series so far (besides maybe Badd), but it’s hard not to warm to him by the end of Clouded Kokoro, given that the man just seems to be under a lot of stress. In Unspeakable Story, we get a better sense of the kind of values that Gregson must have, something that’s only ever really seen again after his death near the end of Resolve.

And so, with Susato called away for Japan, The Great Ace Attorney Adventures comes to an end. On its original release, it would be two more years before the story continued, but luckily, Western fans didn’t have to wait for…

Part Six: The Adventure of the Blossoming Attorney, Susato and the Defendant Defence

The first case of Resolve is ultimately a bit of a disappointment, falling into a pattern set by The Lost Turnabout – it’s short, kind of pointless and ultimately not too memorable, although the villain is kind of fun. It does serve some purpose within the overall plot of Chronicles in reintroducing Jezaille Brett(‘s corpse), tying up the fate of characters like Sōseki and reintroducing Mikotoba and Judge Jigoku. However, everything else is just kind of there, including a weirdly hyped up “best friend” character for Susato, who ends up being almost entirely uninteresting and irrelevant.

However, this case can prove useful as a springboard to discuss two more relevant topics. The first is Susato, who in this case is forced to dress as a man in order to stand as a defence attorney in the court of Japan. Susato is, in fairness, a pretty different kind of assistant to the ones that have come before. Instead of being the younger, more naïve Maya-like, Susato is actually the more mature and knowledgeable character compared to Ryu, which leads to a slightly more interesting dynamic of Ryu having to often rely on Susato for help because of her superior intellect rather than just their friendship or any kind of magic ability. It’s nice to see Takumi writing a female assistant character in a way that doesn’t just fit the same peppy fun archetype, although Susato can sometimes lean slightly too much into it.

However, the bigger problem is that he sometimes doesn’t really know what to do with Susato. Her devotion to Asogi and the fact that you have to win her over makes her appearance in Unbreakable Speckled Band the most engaging, but after that any sort of plotline for Susato kind of fizzles out. Any attempt to give her moral complexity in Unspeakable Story is removed by the fact that she’s absent for most of the case and is so heartbroken by having done something slightly against the book that it almost destroys her ambitions in the law. Even in Blossoming Attorney, which is ostensibly her case, Susato is the least interesting part of it, save for her friend Rei Membami. Despite Susato’s legal prowess and calmness under pressure, Takumi can’t help but write her in an almost identical way to the way he writes Ryu in Great Departure, replete with the same wild eye animation that seems strangely out of character for Susato.

The other interesting thing is what I referred to in this part’s title as the defendant defence, and it’s a way of removing complexity from Ace Attorney that is noticeable in all games but comes up a lot in Chronicles. To understand this, let’s first make the assumption that while all killing is wrong, some killing is worse than others – it’s pretty much okay to kill in self-defence, but it’s morally wrong to take the life of someone innocent in a carefully constructed plan. The victim of Blossoming Attorney is herself a murderer – in fact, she’s a hired assassin. She’s also a virulent racist and has been found guilty of murder in Great Departure already. In that case, the punishment for her guilt is to be sent for execution by the state, but she manages to evade it because of the political manoeuvrings of Lord Stronghart. Thus, the game has already decided she deserves death. The culprit of Blossoming Attorney is Raiten Menimemo, a journalist who has taken the case into his own hands and done what we fought for the government to do only a few cases earlier.

Now, I personally condemn most killing, including that carried out by the state, but this isn’t the position Ace Attorney tends to have. So, in that case, and using Ace Attorney’s standard of morality, can we really condemn Menimemo? The answer is kind of complicated, but Blossoming Attorney dodges it completely by having a cute, smart female defendant. Of course we hate Menimemo – he tried to frame this nice clever young girl. This is the crux that Ace Attorney time and time again uses to dodge this moral issue, but it’s worse in Chronicles because it’s a game that keeps bringing it up and trying to discuss it; the whole concept of the Reaper and the Professor are people who kill bad people that the courts cannot touch, but because of Stronghart’s overt villainy, the game once again conveniently uses its get out of jail free card. What’s worse is that it keeps hammering home the message that Menimemo has become as bad as Brett. This takes an incredibly essentialist stance on the topic of murder – all murder is equally bad, and thus Menimemo and Brett are at the same level. But because the series already tacitly endorses state killing, this becomes at odds with its overall values. Again, this is a problem throughout Ace Attorney but seems especially bad in Chronicles, which brings it up again and again.

Part Seven: The Reaper of the Bailey and The Return of the Great Departed Soul

The Return of the Great Departed Soul is where The Great Ace Attorney finally gears up for a conclusion, introducing elements like the return of Asogi, the mystery of the Professor and Courtney Sithe and the stronger hints of darkness at the core of the British legal system. It’s also the first case that really strives to give some more depth to Barok van Zieks before he’ll become the defendant in the next trial.

Van Zieks is what you’d refer to as a competent prosecutor in Adventures, but there’s a definite sense that Takumi is holding himself back from giving him much depth before Resolve. In fact the two main character traits he’s given in the first game are his alcoholism and his racism, neither of which particularly endear him to the player. His arc at least doesn’t follow the Edgeworth model as strictly as someone like Nahyuta. From the first time we meet him he’s clearly already trying to seek the truth above all else and rooting out the corruption in London’s streets is his goal throughout both games. What does change is his respect for Ryu and his coming to terms with the fact that the things he’s believed the whole time; like that the Japanese are untrustworthy and that his brother was a saint, are wrong. Basically it’s an arc of challenging assumptions, and it’s lucky that the game is set when it is, because any modern day interpretation of this character would be almost entirely unsympathetic. However, as it stands, Takumi is generally adept at finding the humanity in Barok’s racism and tying it into a message that seems to value the effect of personal relationships as the great leveller and the way forward to achieve an end to discrimination. Of course, read one way it does all become a bit Green Book, where just meeting one nice non-white person is seen to be enough to change the heart of an old racist, but Van Zieks has fun enough animations and warms up to Ryu in a grouchy-but-loveable enough way that it’s easy to gloss over when you’re actually playing the game.

Asogi returns in this case as Van Zieks’ apprentice, and luckily the lid is lifted off that badly kept secret pretty quickly. His relevance to the game ties into the events of 10 years ago, an infamous serial killer called the Professor, whose resurrection in a London cemetery forms much of the backstory to Great Departed Soul. Takumi, it appears, seems unable to quit the drug that is “that mysterious case that happened around 10 years ago”, and the Professor case in particular comes to bear some similarities to the Joe Darke killings from Rise from the Ashes. In this case, it was an already-exhausting-to-hear way to tie together almost all the characters and incidents that the game had already introduced, the spectre of Trials and Tribulations that I’ve mentioned previously looming large again.

I mentioned when talking about the jurors that their reuse had the unfortunate side effect of making London seem small, but actually nothing does that more than the kind of interconnected case that the Professor incident embodies; a similar problem to what happened in The Grand Turnabout. The Great Ace Attorney does mitigate this problem slightly with a lot of small one-off characters that appear together on the stand – people like Gotts or Sandwich that aren’t encountered in investigations but appear only in a couple of cross-examinations early on. This does mean that London ends up seeming a bit bigger, but it also means these characters become incredibly throw-away and unmemorable. I’m glad that Gotts wasn’t tied into the backstory of this case but his insignificance means that the overall effect is the same – everyone that counts, from the victim Asman to the killers Drebber and Sithe to the witness Madame Tusspells, were connected to the events of 10 years ago. To properly fix this issue, some more memorable supporting roles would have been needed. As it stands, when I saw Asman’s name on the newspaper drawing, I couldn’t help but groan.

Part Eight: Twisted Karma and His Last Bow, The Resolve of Ryunosuke Naruhodo and Variations on a Theme

I didn’t talk too much about Great Departed Soul simply because the final three cases of Resolve tie into each other in a way that makes discussing them all individually rather unsatisfying. The only really unique element about Great Departed Soul that doesn’t occur in the other cases is the plotline of Drebber and Harebrayne, and while both are brilliantly animated characters, their underlying plot simply becomes another variation on Chronicles’ obsession with the themes of revenge and people becoming the things they hated.

Twisted Karma and His Last Bow and The Resolve of Ryunosuke Naruhodo are actually two parts of the same trial, but they have different enough atmospheres that the decision to separate them does make sense. Twisted Karma is probably the better of the two, starting as a Turnabout Corner-esque collection of odd tasks around London and culminating in the slow revelation of some of the darker histories of the game.

The victim this time is Detective Gregson, with Van Zieks accused as the killer. Of course, this allows for a softer side to be shown for Van Zieks but it also gives Gina, whose previous appearances have been slightly too predictable in showing her character progression, some more pathos to work with, as well as giving Asogi the prosecutor’s bench all to his own.

Asogi is a great prosecutor in both cases here, because his ulterior motive for taking the case – to clear his father’s name and get revenge on Van Zieks, is so cripplingly clear. Before these cases Asogi is built up to be this kind of legendary, amazing person – so much that too much dialogue is taken up telling the player what a legend and a good lad he was, even when it’s not fully supported in the full amount of screen time he gets. When Asogi actually gets the bench to himself, however, the image of him that has been hammered into your head is slowly broken down to reveal a far more interesting character; someone broken by the events of the past and on a kind of manic, self-destructive path for revenge. The reality of people you admire being more complex than you might imagine is seen through characters like Gregson, Klint and Dr. Sithe for some other characters, but Asogi is the betrayal that the player themselves best gets to experience first-hand. Asogi is driven by the same quest for the truth that drives most Ace Attorney characters, but he’s too close to the situation to be able to actually do this. It’s only through a more level-headed and well-trained Ryu that he’s able to find the salvation he’s searching for. One particular moment I’d like to commend is Asogi’s breakdown in the final case, showcasing a kind of mad anger that is usually reserved for criminals in the series. When Phoenix or Ryu, or even Apollo break down, it’s a kind of despair. When it happens to Asogi, he’s allowed genuine frustration and anger, a cathartic release that Ace Attorney writers often deny their protagonists in an effort to make them more relatable – so it’s good to see Takumi allowing Asogi to let loose here.

Another fantastic character that gets some time in the spotlight in these two cases is Daley Vigil, who was the former chief warden at Barclay Prison at the time when Genshin Asogi was imprisoned there. Vigil is a victim of government scheming and loses his job after being accused of aiding in Asogi’s escape. After that, too ashamed by the loss of his job and status, he goes into begging during the day, eventually finding a job only after Gregson takes pity on him. Vigil reinforces the theme that the Garridebs first brought up – that of the dignified face of British society that has to hide an underbelly of poverty. Even better, Ryu revealing Vigil’s secret to the courtroom raises the ethical issues of whether it’s right to drag someone through the mud in the name of finding the truth, a similar problem to what happens with Adrien Andrews in Farewell, My Turnabout. Vigil is a victim of all those involved, including Ryu and Asogi, who both end up apologising to him.

Although Vigil reintroduces the class theme that had been present in earlier cases, it’s safe to say that any idea of this being one of Takumi’s main ideas when coming into Chronicles is abandoned once you see that neither of the finale cases have a jury. Of course, this is a disappointment because the summation examination mechanic is enjoyable but only actually gets used in two of Resolve’s cases. However, on a wider scale, this means that Takumi completely steps in the wrong direction when it comes to the indictment of Lord Stronghart.

Stronghart himself is a villain almost entirely ripped from the Damon Gant playbook, right down to the orange double-breasted suit. Gant is an interesting villain, and while Stronghart suffers a little from being such a carbon copy, he’s still not uninteresting, although the game treats him a bit too much like a cartoon villain to properly examine his motivations. But without a jury there’s a missed opportunity to make him stand out from Gant. Sure, Stronghart is able to get the British Judiciary on his side – that’s because he’s one of them. But with a jury of the common man there, an upper-class judge deciding on the people’s fate and keeping them in the dark of the operations of the judicial system might actually be a harder sell for Stronghart. There are great themes of how the ruling classes in Britain patronise the working classes, but without any working-class representation in the courtroom, the game fails to explore them. Instead, Herlock convicts Stronghart with the help of Queen Victoria, known champion of fairness, justice and equality. Great.

The game also falters when it addresses the problems of the British Justice System in general. In fact, it isn’t ever quite sure what the problem is. In the final case, the darkness at the heart of the courts is decided to be the Reaper of the Bailey, who has been taking justice into his own hands by cleaning up the streets of London of criminals. However, attributing the problems with the British justice system to the Reaper is almost worse than attributing the Dark Age of the Law to the Phantom; the Reaper is nothing more than a by-product of the real problem, which seems to be the power of money and influence exerted by characters like McGilded and Asman that allows them to circumvent the law. The Reaper is indeed a problem, but it’s hard to say that the Reaper is the problem. In Clouded Kokoro, Shomes notes that one problem in the British courts is the jury, who can sometimes let guilty people escape. Indeed, this is a problem with juries in real life as well, but Apollo Justice proved that the jury can have additional advantages not shared by the evidence based system other courts in the series work from. Unfortunately, Chronicles is not prepared to face the complex realities dreamed up by its own previous cases. Instead, it pins all the problems Ryu and co. have seen over the course of their stay in London on one person and allows the Queen to simply make the problem go away.

Luckily, the mystery and the case itself are more engaging than the bloated interconnected plots of a Yamazaki team game. In particular, the idea of the assassin exchange is the kind of fun international plot I wished that Spirit of Justice had tried to do. Every character in Chronicles’ plot have motivations that are easily understandable and fit together surprisingly neatly. Takumi even manages to give some pathos and character to Klint van Zieks, despite him having died 10 years before the events of Chronicles and never appearing on screen in person, besides one written note at the end of the case.

Perhaps the only character who gets short shrift in The Resolve of Ryunosuke Naruhodo is Ryunosuke Naruhodo himself. Ryu starts Chronicles as my favourite protagonist in the series. His wide-eyed panic in Great Departure sets him firmly apart from the other trained attorneys that are playable in the series and his journey to becoming a lawyer and overcoming the prejudice of the British courts is admirable and more in-depth than perhaps any of the previous protagonists of Ace Attorney. Phoenix and Apollo have moments of character development when they’re on the bench, but Ryu stands out in just how much focus is put on him, both in dialogue and in animations.

This is why it’s a shame that he gets kind of lost in the noise of Resolve. Characters with more relation to the events of 10 years ago, like Asogi and Van Zieks are allowed big emotional pay-offs, but Ryu just sort of keeps chugging along while other characters get the fun moments. Even the un-changing Sholmes is allowed a fun toe-tapping reunion with the real Watson, Susato’s father Mikotoba, in this case, while Ryu doesn’t get anything. The most he really has to do is remember to ring Sholmes when things get too tough. Despite the case’s title, Ryunosuke has to show less resolve in this case than in the first case of Chronicles.

Conclusion

This, perhaps, is my problem with The Great Ace Attorney: Resolve in general. Adventures, despite having some issues, does have a desire to do things a bit differently. There’s a greater emphasis on characters, on adding more depth to the ideas of past cases and of generally creating a kind of Ace Attorney game that feels a bit different. It doesn’t always succeed on achieving those goals, but you get the sense that Takumi is trying to strike out, even a little.

Ultimately though, by the time the sequel comes around, nothing that Adventures tries to do is kept. The Great Ace Attorney: Resolve plays like a new Ace Attorney game. It seems odd to criticise it for that, but it remains the case that a new Ace Attorney game isn’t quite good enough when the first half has visibly struggled against that. Much like Spirit of Justice, The Great Ace Attorney: Resolve keeps trying to strike out into new fields but is ultimately too reverential to the series’ past. Almost everything in that game is a retread of themes and cases that have been and gone; sometimes done better but often done worse as well. On top of that, it’s also a game that struggles under the weight of its narrative ambitions, often bringing up interesting ideas only to disappoint by having to rush their conclusions.

At the end of my last Ace Attorney post, I noted that the mainline series’ move to larger stakes and away from more personal stories dimmed my interest in a continuation of that storyline. In The Great Ace Attorney Chronicles, one can almost see that play out in miniature. I personally think that Takumi still manages to balance personal stakes with large plots better than the games of Yamazaki’s team. However, the baseline problem still remains. I don’t think Ace Attorney will ever move back into a realm where I can’t criticise it for this – the tone of the games makes them unsuited for tackling the larger moral issues they bring up in these huge, political conspiracy themed cases, but the series’ overarching plots are lauded too much for them to move backwards into the small scale. However, I do take some solace in the fact that these games can still appeal to my particular sensibilities in cases like Clouded Kokoro. For now, I’ll hold onto that and wait to see what the next instalment brings.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you enjoyed the return to writing extensively about Ace Attorney. As always, if you liked this, you can do me a huge solid and follow me on twitter or donate on patreon.

While I definitely think I have a more positive view of this duology than you, I do definitely agree that I think Ace Attorney is better when it focuses on more personal narratives rather than trying to be about these large international conspiracies, which can be entertaining, but often don’t fit well with Ace Attorney inherent nature. I also am curious, do you prefer either game or do you see them as equal/don’t really like seeing them as different games? I’m sorry if this was actually made apparent in the review, but I honestly am not sure after reading everything you’ve written. I personally prefer DGS1 because I liked that a majority of the game focused more on personal stories rather than what DGS2 did, but I can also understand why so many prefer DGS2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oooh good question – on this playthrough I kinda grouped them together in my head, but when I played them individually I preferred the first one by far. The first one tries new stuff more often, has smaller stakes but an interesting mood of conspiracy throughout, while the second one can get too grand and bogged down in the spectacle of it all. (TGAA2-2 is my fav case in both, though)

LikeLike